Archive for the ‘Behavior’ Category

Asking the Wrong Questions

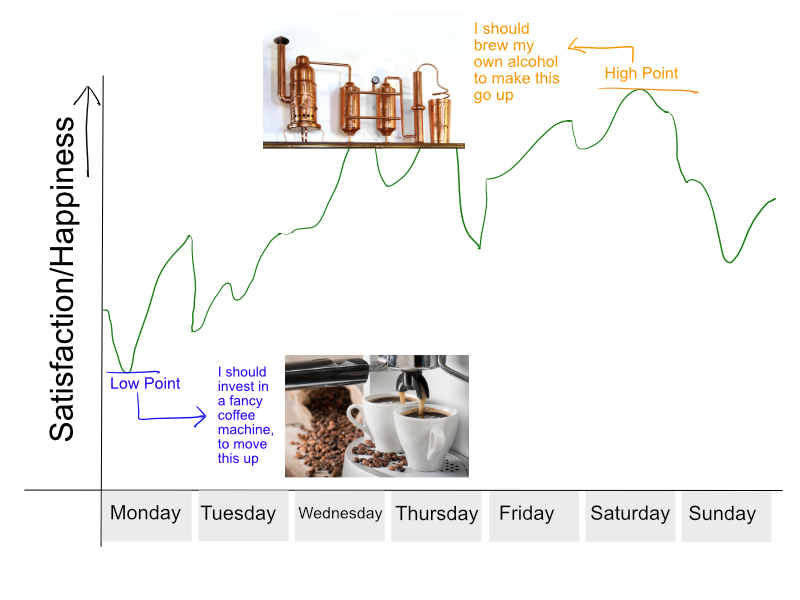

One question I like to answer myself essentially poses itself is the personal investment question: if I had some extra time, money, wishes, etc. Would I put them into making the best hours of my week better? Or would I put them into making the worst hours of my week better?

For example, should I buy a new coffee maker, so that my morning coffee on my way to work is better? Should I buy new headphones so that I can listen to music in bliss while I work?

Or should I put that money into an attachment for my bike, so that when I go for a bike ride, I can capture video of it. Or should I instead buy tickets to a fun concert for me to attend on the weekend?

Knowing this goal is somewhat useful knowledge. For example, if I’m already energized at work maybe the coffee doesn’t make sense, or if I look forward to interacting with my workmates, maybe the headphones don’t make sense.

Alternatively, if I’m constantly worried about work, the concert could either be a great distraction, or it could be pointless if I’m going to obsess about the work I have to do anyway.

Thing is, this question of optimization is pretty limited. And, in fact, it might actually be in the way of my happiness.

There is another alternative: maybe neither the best hour of my nor the worst hour of my week need fixing. I posit that viewing life itself as an optimization problem is a problem itself. (Well, maybe not a problem, but certainly a short-sighted distraction.)

This constant need to improve ones’ life is itself an incessant treadmill. You’re constantly looking for the best deal on what you need next. Or you feel like you don’t have enough time to do the project you set out to do that will make life (the best or worse moments) better.

Instead of buying better headphones, enjoy the ones you have.

I’d place this seemingly logical question in a class of questions which seem like they are useful, but are really an artificial mental construction which doesn’t necessarily have any grounding in reality. But, since we thought the thought, it’s hard to admit (or understand) that the question itself can be dismissed, that it was conceived in our mind, and isn’t indeed part of the world around us. Usually, “Why did so-and-so do that?” fall into this category: trying (or pretending to try) to explain someone else’s behavior when we have our own mental model.

Finally, optimizing on a week-by-week basis is also arbitrary. Maybe the best thing you can do is to forego any change for months, so you can incrementally get to a better point in a year. (I picked a week here, because most people have 5 work days and 2 weekends, so you see the contrast between the best and worst times during the course of a week.) Things that have made me truly happy usually took longer than a week.

Frozen Lake

True contentment is a thing as active as agriculture. It is the power of getting out of any situation all that there is in it. It is arduous and it is rare.

— G.K. Chesterton (via Moment of Happiness Daily Quotation)

Work is busy. There are many things, each of them detailed investigations, that need to get done in a short amount of time. Customers expect that from us–and our competitors.

Normally, at lunch time, I’ll stay in and eat at my desk, usually surfing the web while doing this. Today, I decided to take a walk outside.

Outside was warmer than I expected, but still crisp. Yet, the pond was frozen. An usual but serendipitous combination. I took a nice, refreshing walk. I stretched on the grass.

I immediately forgot what was going on in my office. My mind cleared.

Today, getting all there is out of a frenzied situation means creating a calm moment.

You only get one chance to agree

When someone presents you with a new idea, you have all day to disagree.

When someone presents you with a new idea, you have all week to disagree.

When someone presents you with a new idea, you have all month to disagree.

When someone presents you with a new idea, you have all year to disagree.

You only have one chance to agree. One chance that matters.

People want to be heard. Don’t argue. It’ll be okay.

Catharsis « You Are Not So Smart

Thanks to Freud, catharsis theory and psychotherapy became part of psychology. Mental wellness, he reasoned, could be achieved by filtering away impurities in your mind through the siphon of a therapist.

He believed your psyche was poisoned by repressed fears and desires, unresolved arguments and unhealed wounds. The mind formed phobias and obsessions around these bits of mental detritus. You needed to rummage around in there, open up some windows and let some fresh air and sunlight in.

The hydraulic model of anger is just what it sounds like – anger builds up inside the mind until you let off some steam. If you don’t let off this steam, the boiler will burst. If you don’t vent the pressure, someone is going to get a beating.

He was wrong. Read more here: Catharsis « You Are Not So Smart.

Or buy this book.

Epicurus: a pre-cursor to positive psychology?

I’m partway through the book The Consolations of Philosophy by Alain de Botton. I’m amazed by a couple of teachings of Epicurus:

- Wealth does not necessarily mean happiness. (In fact, relishing simple indulgences tends to make one happier than acquiring a sophisticated taste.)

- In order to be happy, you should surround yourself with friends.

This reads straight out of Seligman’s Authentic Happiness (among other places). So, basically, it took thousands of years for psychology/philosophy to re-deliver an ancient truth.

Cognitive Dissonance Mashup: David Allen (GTD), Gary Marcus (Kluge), Martin Seligman (Authentic Happiness)

I really like David Allen’s Getting Things Done. While he discusses long-term (50,000-foot) goals, he focuses on the near-term panic-causing stressors of an over-demanding life first. Someone who is just plain stressed out isn’t going to start thinking about their life vision. He clearly understands the needs of and stresses on the human brain. This (at least in my lay opinion) is the power of cognitive behavioral therapy as opposed to psychoanalysis: who cares about what happened years ago if you’re just nervous/sad/pissed about what is happening now.

Assumptions vs Accomplishments

I’ve been lucky enough to find myself in a team that’s intent on finding the best circuit design for a given application. This doesn’t happen often to many people, but I feel that I’ve had more than my share of this opportunity.

The conclusion is usually that we come up with some topology (let’s call it circuit X) that optimizes all the performance criteria. I walk away wanting to generalize the experience with the lesson that circuit X is the best circuit ever, and I want to use it everywhere.

Inevitably, I find that some other topology Y is better suited for some other application. There were some specific constraints or conditions on circuit X that don’t apply to circuit Y, and as a result, circuit Y is more optimal for application Y.

Looking back on this behavior, I think the main fault is the tendency to remember only the conclusions and not the assumptions. Why do we* do this? Well, because the assumptions are where we start. The lesson learned is where we end. We’d rather remember the finish line—the victory—rather than the starting line. It’s certainly more glorifying to remember your accomplishments rather than the mundane criteria that drive us to the goal. We are also rewarded for the results, not the specification of the problem.

I’ve periodically re-learned this tendency to form generalizations by forgetting assumptions and by only remembering the conclusion of the thought process.

footnotes

* Maybe I should say I, not we: perhaps I am generalizing again.

What Makes Us Happy? – The Atlantic June 2009

Interesting (albeit long) article on a very large psychological study spanning many years:

As Freud was displaced by biological psychiatry and cognitive psychology—and the massive data sets and double-blind trials that became the industry standard—Vaillant’s work risked obsolescence. But in the late 1990s, a tide called “positive psychology” came in, and lifted his boat. Driven by a savvy, brilliant psychologist at the University of Pennsylvania named Martin Seligman, the movement to create a scientific study of the good life has spread wildly through academia and popular culture dozens of books, a cover story in Time, attention from Oprah, etc..

Vaillant became a kind of godfather to the field, and a champion of its message that psychology can improve ordinary lives, not just treat disease. But in many ways, his role in the movement is as provocateur. Last October, I watched him give a lecture to Seligman’s graduate students on the power of positive emotions—awe, love, compassion, gratitude, forgiveness, joy, hope, and trust or faith. “The happiness books say, ‘Try happiness. You’ll like it a lot more than misery’—which is perfectly true,” he told them. But why, he asked, do people tell psychologists they’d cross the street to avoid someone who had given them a compliment the previous day?

HarvardBusiness Study: 10% of twitter produces 90% of tweets

I just read New Twitter Research: Men Follow Men and Nobody Tweets – Conversation Starter – HarvardBusiness.org.

A few things strike me about the results:

- It meets the

80/2090/10 rule. - Twitter is basically a broadcast service–not a one-on-one messaging tool.

#2 strikes me because I’ve always seen myself as an outsider. I’ve always felt that there must be a large contingent of twitter users that use twitter to tell their friends where they’re meeting for drinks tonight.

I’ve told friends that the only thing they’ll get from me on twitter is spam. (That’s a bit facetious: I’d like to think that my blog posts have intellectual value that informing people that they can proffer money in exchange for retail products advertisements do not.) If I were a corporation, they’d be filled with tons of marketing.

I suspected that I’m not getting this utility out of twitter because my friends aren’t on there, sharing in dialog.

What I realize now is that there’s a sort of myth behind twitter: it’s generally being used as a broadcast medium. In that respect, it seems less useful for my socializing: I don’t really care what most of my friends are doing each night in Chicago. I’m not in Chicago most nights. If I have a night available to meet up with friends, I’ve already pre-arranged it.

Incidently, I learned about this post from http://twitter.com/HarvardBiz/status/1995340326

Brief timing statistics of my vote this morning

I voted early this morning. I thought it might be better to go in today rather than on Tuesday. I wasn’t the only one. There was a long line of people at the early voting place this morning. (This isn’t the same place that they conduct regular elections on voting day.)

Many people saw the line and just decided to come back later (I hope). Anyway, the quantitative analyst geek that I am, I started timing how long it took. I started the timer on my wristwatch and started counting people as they left the polling place.

In 45 minutes, I counted 38 people. That’s 1 minute 11 seconds per person.

The process was as follows:

- Wait in line for about 50 minutes

- Wait at the door of the voting room until there’s an open spot at the table

- Go to the table and sign a little sheet of paper; hand it to the clerk

- The clerk at the table compares your signature to your photo ID and looks up your name in the database

- You are given a 4-digit access code by another clerk

- You wait for an available voting machine

- You punch in your access code into the machine

- You vote

- You confirm your votes, see a print-out scroll through a window confirming your votes

- You leave

There were 4 voting machines at the polling place. This number is likely a lower than would be there on election day, so it’s likely that things will get done quicker on election day. For example, if there were 8 machines, I’d imagine that they could process votes at a period of 36 seconds per person.

The clerks who had to sign me in and hand me the access code wasn’t a bottleneck at all. It took people longer to actually vote at the machines (4 at a time) than it took the clerk to process people coming in. But we can safely assume that there will be more people around on election day. Keeping the ratio of clerks to voting machines at 2:4 would be safe. So, to process 36 seconds per person, they would need two clerks and 8 voting machines. Let’s hope they have enough.

In total, it took me about an hour from when I got in line to when I was done voting.